DANGEROUS ARCHIPELAGO

TUAMOTU’S: FRENCH POLYNESIA

Story by Jon Bowermaster | Photographs by Pete McBride

The Tuamotus are 78 distinct coral reef atolls, stretching 930 miles north-northeast of Tahiti. From a distance the islands come and go from sight, thus the nicknames ‘the Labyrinth’ and ‘the Dangerous Archipelago.’

SHARK CITY

C

’mon friends, follow me, c’mon, meet my pets,” Ugo shouts, tossing another chunk of bloody bonito into the quintessentially-cobalt South Pacific. “The heads, that’s what they like best.” A gentle big-man, smelling of gasoline and sunblock, his solid, sun-browned body quakes with excitement as he dips his hands repeatedly into the white plastic bucket of fish-parts resting on the back of his 40-foot cutter “Oviri” – Tahitian for “Wild” – bobbing in rough seas.

With each handful of chum come more carcharinus melanopterus — black-tip sharks – two dozen, three dozen, 50, 100, 200, so thick it’s impossible to count them, to separate them, for all their swarming and churning just below the surface. With hands like catcher’s mitts Ugo pulls off his clear plastic sandals, replaces them with swim fins, and reaches for his mask and snorkel.

“They’re waiting for us,” he shouts as he jumps smack into the midst of the swarm. He is so positive – so convincing that there is nothing to worry about, being inches from the snapping choppers of eight-foot long, 400-pound sharks even as he continues to toss them bloody fish parts, despite that he’s missing part of a thumb for having gotten “lazy” during one such feeding – that I follow. When I open my eyes, four-feet below the sun-sparkled surface, there are literally hundreds of big sharks circling. Me.

“Look, down there,” shouts Ugo when we surface. “Lemons! Big ones! WELCOME, MY FRIEND, TO SHARK CITY!”

Ugo is a true man of the sea. He has three boats and a simple beachside house on the lagoon of Rangiroa, the world’s second-largest coral reef atoll and the best known of the 78-atoll Tuamotu chain north of Tahiti. His father was a local hotelier. Ugo, 36, speaks good surfer’s English because half his life ago his father handed him a check for $30,000 and a plane ticket to San Francisco. “Go to UC-Berkeley, get an education, learn English,” was his directive. He followed orders . . . but only halfway. Days after arriving in the U.S. he discovered Half Moon Bay, bought a board and made surfer friends. Two years into his scam – complete with phonied “reports” from school – the gig was up. His punishment? Live, and live off the sea, on this beautiful spit of coral-and-sand-and-rubble here in the dead center of the South Pacific.

“Not so bad,” Ugo laughs. From the back of the “Oviri” Ugo continues to play. Baiting a 50-pound baby black-tip with a fish head tied to a plasticized line he pulls it, thrashing, into the air. The struggle lasts 30 seconds before the shark opens its mouth – wide, exposing a long line of fine, sharp teeth – lets go and swims off.

Flicking pieces of bait off his forehead with a giant finger, Ugo grins, his smile as wide as the shark’s mouth. “This, my friends, is paradise! No?”

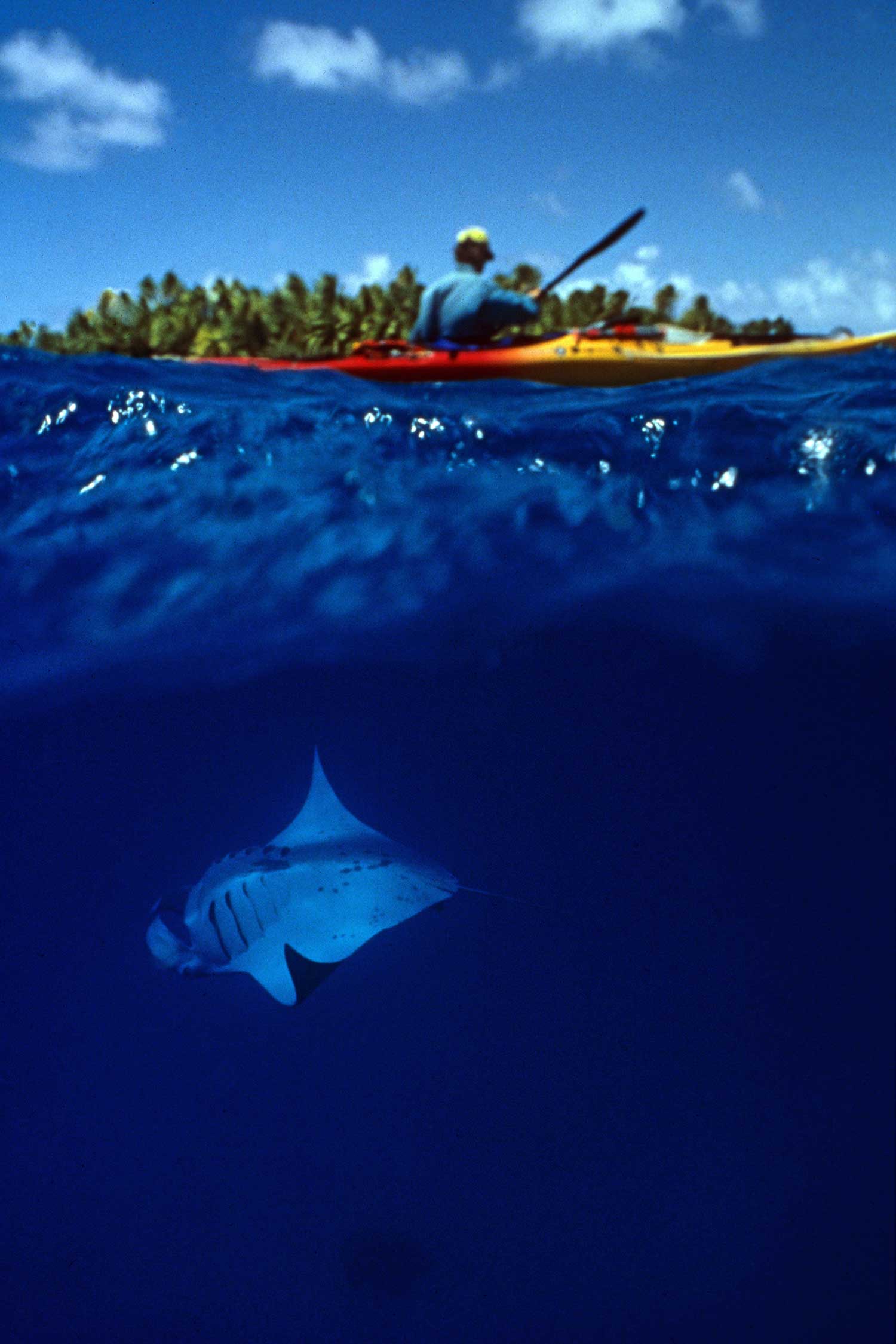

The very best way to explore Polynesia, of course, is by sea kayak since this part of the world was initially explored by men in small boats. This 2002 adventure was the third of our Oceans 8 Expeditions, sponsored by National Geographic, which would over a decade take us around the world by kayak, one continent at a time.

NOBLE SAVAGES

A

pair of taxi-boats works the dock at Avatoru, where we slip our kayaks into the northern rim of Rangiroa’s 50-x-20-mile lagoon.

One taxi-man, sixty-something, is covered head-to-toe and all parts in between — everything but his tongue — by tattoos. They tell the story of his life, and his family’s. Diminutive and bow-legged, graying ponytail pulled back, he wears surfer shorts and a yellow slicker to keep the salt-spray off during his dozen roundtrips between motus each morning and afternoon, delivering school kids by community cigarette boat. Astride the bow, guiding him among the corals and jumping dolphins, rides a dread locked man in matching uniform. He is younger and thus his life-story, via tattoos, is a work-in-progress.

Bruno commands the second taxi. A fat man in a torn blue t-shirt and a shock of windblown black hair, he motors back and forth to Tiputa in his 10-foot-long taxi boat, often empty, trolling simultaneously for clients and fish. Docked, he shouts to the nearby sandwich joint for a “fishwich and a Coke.” And then drops his cell phone into the drink. FUUUUCCCKKK!!!! The school kids gather around, laughing. Bruno laughs too, strips down, and dives for his phone. His mother sits patiently on the dock waiting for him to take a big parrotfish for their dinner. Turns out Bruno is a man of big ideas, including a screenplay. “A Paumotuan in Manhattan” he calls it (the islands are the Tuamotu’s, the people, Paumotuan’s). “Take a simple fisherman and, via genetic-transponder or something, have him reemerge whole in the heart of New York City, spearfish in hand.

“Who do you think should play the Paumotuan,” he wonders, pacing up and down the cement dock. “Maybe Brad Pitt?”

It is a gray morning in paradise, which happens. And these are the modern-day Noble Savages.

It was the English poet John Dryden who coined the phrase, but Frenchman philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau who, in the 17th century, got famous for it. It was a time when many European thinkers were preoccupied with questions about what was basic to human nature. The argument was also being put forward that perhaps civilization of the Western kind was a crushing weight that produced deformities in humanity. There must be a simpler, nobler way of life – and a better, simpler, more noble man – went the argument.

Hand-in-hand was the desire of exploring Europeans of the time, especially those beginning to round the globe by sea, to find some kind of earthly paradise. And its perfect people. Columbus, when first-sighting the Caribbean islands, was convinced he’d found it. Black Africans failed to be perfect; Chinese, Persians and others were disqualified for being “too civilized.” British explorer Samuel Wallis was the first white man to land in Tahiti, in 1767 and his sailors were the first to become “madly fond of the shore” here. Arriving six months later was Frenchman Philibert Commerson who first publicly claimed he’d discovered the Noble Savage.

A naturalist aboard the ship of Louis Antoine de Bougainville, Commerson was also the first to label the South Seas “utopia.” In the two-and-a-half centuries since, sailors from Fletcher Christian to James Cook, writers from Robert Louis Stevenson to Jack London, painters like Gauguin, novelists like Melville and tourists by the tens of thousands have followed, all searching the same: Heaven on Earth.

The results have been mixed. For a brief moment in the 18th century the Polynesian seemed to offer the white man a vision of what it might be like to go naked in the world once more. The idea of some sort of earthly paradise in the South Seas lived on into the 19th century. It was by its nature inextinguishable, irrepressible. But the image changed; those who wrongly continued to believe that savages could teach civilized men how to live were more and more regarded as maladjusted.

The Noble Savage was of course a fiction. Still . . . ask Western man today – Anyman – to paint a picture in words of Paradise. A high percentile will include in that tableau island beaches, azure skies and seas, coconut palms. Those things are still the foundation of utopian-dreams and do they exist here in Polynesia, as they have for a million-odd years.

We’ve come with kayaks, to glimpse this particular paradise up-close. Two months, a third of the Tuamotuan atolls, some populated, others not. This most-remote chain lies perfectly halfway between Australia and South America, 3,500 miles from each, and was given the nickname “the Dangerous Archipelago” by Bougainville, thanks to the shallow, sharp reefs that surround the 78-atolls spread west-to-east over 1,000- miles. Hundreds of navigators before us, searching for their own paradise (or plunder or new-economy) ran aground here on this spiky edge-of-the-world speed bump, no doubt cursing this place as something other than utopia. Magellan was the first westerner to map the chain, spying eastern-most Pukapuka in 1521; 300 years later when the atolls finally succumbed to the French Protectorate there was still a handful of cannibals living about. Life since has been mostly peaceful, but for the French testing their nuclear weapons on the atolls of Muroroa and Fangataufa until 1997.At our day’s end, following an 18-mile crossing of Rangiroa’s interior lagoon, we paddle into the shallows on its southern side, skirting “micro atolls” forming just below the see-through surface on the sandy bottom of the lagoon. Coral build-up, resembling giant wagon wheels, they are studded with the snake-like blue/green mouths of encrusted clams sparkling like jewels under a navy-blue sky.

Camp is set on a virgin, no-name beach, alongside a hoa – a pass running from the ocean into the lagoon, but not wide enough to allow traffic in and out. Access to the interior of these atolls comes, if it comes at all, through a single natural pass, maybe two. Lining the reef on the oceanside are prehistoric, sharply- barbed fossilized spikes, eight-foot tall feo lining it like 2-million year old barbed wire. Walking, carefully, through the deadly coral all I can imagine is the fearsome swim of the shipwrecked as they tried to negotiate their way to safety through this natural checkpoint. It would have been a bloodying swim, an ultimate test of desire for those seeking a perfect world.

Arriving by sea kayak we were always warmly met, especially by kids. They were curious about what our boats were made of (plastic), why they were such bright colors (for safety) and how a bilge pump worked. Here videographer Alex Nicks hosts some curious new friends.

SELF SUFFICIENCY

A

white tern, some four decades ago, delivered the announcement of Hinano’s birth.

Her mother, living on the tiny atoll of Nukutavake, was pregnant, and unwed. To avoid undue scrutiny, when the time came Hinano’s great-grandfather paddled his granddaughter across the open ocean in a canoe to the nearby, nearly-deserted atoll of Vairaatea, where the birthing took place beneath blowing palms. With no formal way to make the birth public – thus official — grandpa wrote the date and the name of his new princess on a piece of paper ripped from a sugar sack. Snaring a bird, he wrapped the note in paper money and tied the small bundle to its wing with a strand peeled from a coconut husk. The announcement was found weeks later and official registry of the birth recorded.

“Then, when I was 4, my great-grandfather insisted my mother take me away from the Tuamotu’s, to Tahiti, so that I could get a good education,” Hinano explains. “There were no schools here at the time and that’s what he wanted for me, more than anything. As well as a husband outside of my extended family.”

The result is a most self-sufficient modern-day woman. Dark-eyed and dark-haired, she laughs infectiously while telling her story, all the while plaiting and weaving. Palm fronds into plates, baskets and serving platters, pinwheels & whistles for her five children, white tiaras into coronas she wears each morning on the beach. During this day she will catch and clean parrot and surgeonfish, construct an under-the-sand oven, use dried coral as fire-starter. She opens coconuts with a machete in five practiced whacks and grates the meat into salads of manioc, breadfruit and poi. Kneeling in the shallows, atop a micro-atoll, with a sharp knife she digs clams out of the rock, sharing them raw, drenched under squeezed lime. All the while she’s explaining, in one of five languages, the history of her culture, the Paumotan culture, which she is devoted to protecting, documenting and spreading. She is la modern-day siren — after dinner she will dance, for us, for herself, a passion and occupation she enjoyed before becoming an educator, a mother, a historian, and a television personality in her adopted home of Tahiti.

Talk of her lingering culture and the struggles it faces in an increasingly westernized world ranges from property rights to family and traditions, and the blending of cultures – Polynesian & western – and the inevitable clashes.

“Whenever I come back to the atolls . . .. Everything my great-grandfather and other relatives taught me comes immediately back. It is very special here – the ocean, the air, everything feels different, my body is charged. I feel like I belong here.”

“But care needs to be taken, to preserve the life, the environment, the culture here. The Paumotuan language is already lost, in part due to a rush to learn French and English. In fact, a generation – my generation – was punished in the French schools here for speaking Paumotuan. Some regulation must be put in place – to protect the fishing, to insure the long-term health of the lagoon. Which is hard because the mentality of the people who have never left is stuck between the old world, and the new. That is the biggest problem in paradise now. No one is sure if, or where, they belong.”

Launching sails on our kayaks was a first for all five of us. We rafted three kayaks together and then put up the inverted triangle sails, which gained a lot of speed on windy days. I’m not sure it was any easier than paddling, but definitely used different muscles.

SMALL CRAFT WARNINGS

T

he inverted-V of yellow plastic strains with the mounting offshore winds, luffing and filling as the kayak veers through a growing chop. Thrice as fast as paddling, sailing 18-foot-long kayaks tests new skills, primarily just the ability to stay upright.

The entire South Pacific – 70 million square miles, covering one-third of the planet — was discovered and first explored by men in small double canoes not much bigger than our kayaks. Known as tipairua or pahi, they were manned by four to 20 men. Utilizing paddles and sails they came from thousands of miles away — from south China, then Fiji, Samoa, Tonga and New Zealand – two millennium ago. Using stars to navigate, currents and tides to guide them when the skies were clouded, they covered vast stretches of open ocean between sightings of land. Rarely did they have any idea what lay over the next curve of the earth. Tahiti was found this way, the Marquesas, the Tuamotus, then Hawaii, and Easter Island, centuries before white man arrived by wooden ship. These remote islands were the very last place on earth to bear the weight of man.

Red and yellow, orange and blue, our small flotilla stands out against the intense indigo ocean, the green lushness of the palms, the bright white of the cumulus and bleached sand. Sails are struck off the motu of Paati, on the south side of Rangiroa. Known worldwide as Polynesian triangles, hung on bungeed-corded poles, they are instantly filled to the max by a 15-mile-an-hour trailing wind.

Mesmerized into near-hallucinatory state by the red tip of the bow plowing through the blue of the sea I think about what it must have been like for those early navigators. In big seas they would batten down all – families, flocks, barrels of vegetables, boxes of seedlings – and ride it out. Garlands of feathers hung from the top of the mast indicating the wind’s direction and strength. Becalmed and beclouded, the best of them could dip a hand into the sea and, using just the feel of the current, steer towards what they hoped would be utopia of their own.

In front of me a flock of brown gents plunges to the surface for food, chattering. Schools of silvery, finger-sized flying fish skip over the bow. Just beneath the crystal-clear surface swim a parade of colorful parrot and butterfly fish, manta and sting rays, great, ugly eels and sharks, always sharks. A trio of dolphins breaks the surface and porpoise alongside for a quarter-of-a-mile. Propelled by strong winds the boat bounds up and down through wind-whipped whitecaps. It is a rare north wind, the kind that generally precedes hurricanes, which, if arrived now, would be very, very early in the season.

Arms aching from being nearly pulled out-of-socket by the strong, wind, the decision is made to rig three boats into a trimaran. Using short bungee and brass hooks, the configuration is an imitation – an honorific — of the double-hulled sailing canoes that were first used to explore these seas. If possible, the ride gets even wilder. Rocketing now, twice as fast as before, through whitecaps and rolling seas, the middle boat constantly on verge of wreckage, makes for much screaming of commands and near-hilarity.

“I’ve ridden wild horses tamer than this,” whoops my true Colorado-cowboy friend, Pedro. ”I’m getting my ass kicked here. This . . . is . . . what . . . I’m . . . talkin’ . . . about . . . . HANG ON!”

Navigating in and out of the coral reefs that rim the exterior of the atolls was tricky. Most atolls had just one pass allowing access to the Pacific Ocean. On many occasions we portaged the kayaks over the reef rather than risk the fast moving waters in the passes, but that came with its own treachery: The reefs were sharp like glass and a slip or stumble resulted in bloodshed. FYI, these photos were taken pre-drone; Pete managed to snag a lift in an ultralight to get these aerials.

CORAL REEFS & GLOBAL WARMING

T

There is a strong possibility that the 78 coral reef atolls (actually 77 thin circles of coral rubble, sand and rock + 1 small lump of a remaining volcano, Makatea) that make up the Tuamotus are not long for this world.

Remnants of a once-magnificent chain of towering volcanoes spread over 1,000 miles, these living, breathing, still-growing reefs – and the lagoons they mostly protect – will very likely disappear in the next 50 to 100 years, thanks to their inability to keep pace with a warming – thus rising – ocean.

Frank is a Canadian-born Irishman from Southern California. Nobody’s fool, he first visited the South Pacific as an UC-Berkeley graduate student and has barely left during the past 15 years. A marine biologist, who went on to administer UC-B’s field station on Moorea, he found himself a Paumotuan wife (at happy hour!), got himself an elaborate tattoo, had kids, assimilated to island life.

Walking along the narrow reef crest near another no-name motu, he bends and pulls a stunningly large pencil urchin from a shallow tidal pool. Holding it high in the air, he admires its size and maturity and gently places it back. Wearing a giant straw hat to protect his Celtic skin, stepping gently so as not to slice sandaled feet to ribbons on the sharp coral, he dodges the fast-moving surf tumbling in off the ocean.

“You know my children are seeing these atolls for the first time in their lives . . . . it struck me this morning that they may not last their lifetime,” he says.

The coral we are walking on is one million years old, minimum. For the moment the crest of the reef is protecting the atolls, the lagoons and the people from the rising seas, increased waves and storms. “If the seas heat up as much as some think they will in the next 50 years – just one or two degrees – waves and storms will override these reefs and ‘take out’ all life here,” he says.

One common mistake is assuming that if the seas warm due to man’s increased dependence – and abuse of – fossil fuels, that the greatest danger is that the seas will literally rise like water in a bathtub. That is certainly a possibility. Here in the South Pacific it’s anticipated they could rise by two to four feet in the next 50 years. The potential for disaster is clear and present in a place where populations — as few as five (Tauere), as many as 1,000 (Rangiroa) – live just a few feet above sea level. A bigger concern is that warm seas will bring more storms and bigger winds and will end life as it is today on these fragile rubble-heaps.

The nastiest storm in the Tuamotu’s goes back to 1906, following the San Francisco earthquake, which triggered a tidal wave that surfed back all the way across the Pacific to wipe out dozens of island populations. Jack London sailed his “Snark” through the Tuamotu’s in 1910 and his story “House of Mapuhi” details a hurricane on Hikeru that killed hundreds, as palm trees heavy with escapees from the storm broke off and sent them to drown in the heaving sea. The last hurricane to blow through Rangiroa, in 1983, flooded its two villages, sending people scampering up the airport towers for escape. Frank has seen locals tie their boats to trees and try and ride out big storms, watched families lash coolers around the bases of palm trees, place their infant children inside, circle around and hang on tight as seas rose to their shoulders.

In somewhat typical island fashion this potential coming calamity is mostly lost on locals. In Avatoru a school bus driver and amateur javelin-thrower was building himself a new home just 45 feet from the lagoon edge. Cement pylons supported heavy I-beams raised three feet above the ground, allowing for rising seas to – hopefully – race beneath his new home.

Asked about the weather, he responds in perfect Polynesian form: “Today was not very good.” What about tomorrow? No reply. It’s a beauty of the Polynesians, like many island people around the globe. Living a simple, isolated life, they don’t like to look much beyond right now. The “future” is too far off.

“Global warming?” the bus driver ponders, scratching his head. “No, don’t know what that is, never heard of it.”

“They live day-to-day,” says Frank, “but the reality is they won’t stand a chance. If tropical storms and hurricanes increase, things here will change very, very quickly.”

Outside of tourism and coconuts, fish is the mainstay of the Tuamotu’s economy. On the left our friend Hugo dove deep to spear his catch, which was hiding beneath a rock. The boat driver on the right showed off a classic above-water spearing: Racing his plywood boat after a school he would accelerate with one hand, steer with his knees, and launch his spear while at full-speed. Amazingly, as soon as he pulled the brightly-colored fish from the sea its color would drain.

DRIFT DIVING

F

ingertips grasp for coral outcroppings, any nub will do. Wet-suited, tank-laden bodies stretch horizontal thanks to the 4 to 5 knot current. Just one small tip-hold is enough to keep you from being sucked – fast – through the underwater pass. Manage to hold on, to stay in one place for even a few seconds and a watery dreamscape lies on the other side of your mask, 130 feet below the surface: Giant napoleon wrasses, hawksbill turtles, manta and eagle rays, angel fish, banner fish, parrot fish, pink soft anemones. Schools of snappers, trevallies, surgeonfish, unicornfish, groups, soldierfish. Dolphins plunge deep beneath the surface, then rocket out of sigh.

Nanoa, one of hundreds of French citizens who’ve chosen to use their birthright to live the good life here, hand-signals in slow motion towards a cave. As we kick inside a giant green eel peeks its head over the lip to inspect us.

From inside looking out into the deep blue a spectacle unfolds. Call it Shark City Deux. Grey reefs, lemons, a hammerhead or two, and dozens of black tips. Too many to count, and who wants to. Arms clasped to our chests, fins gently treading, we communicate with hand-signs and thumbs-up. Nanoa’s drifted into this cave 10,000 times before, yet remains transfixed, inspired. There have been plenty of opportunities for her to leave this remote, isolated spit of sand . . . passing sailors with deep tans and big boats, dive masters headed off for bluer pastures, the lure of family and friends, green grass and lavender in her small hometown in Provence. Yet Nanoa hangs on, sharing a small house on the beach with three others, diving s 12 months out of the year.

Above the surface, it is a cool and rainy day. The Zodiac ride onto the ocean was rough, through standing four-foot waves. Dolphins followed, one leaping six-feet out of the sea. Nanoa, pulling wetsuit over bikini, pointed and wiped a soft rain from her eyes. Looking me straight in the eyes, I expected something profound, pre-dive:

“On ‘three’ we go in, together. Okay?”

I nod, hoping for something more, hoping for a personal invitation to dive deep into her ocean.

“We have 4 tides here, every six hours. Okay?”

And then, lastly:

“Signal me when you have 100 bars and when you have 50 bars. Okay? And when we come up, we come up together. We make a safety stop 10 feet from the surface. Okay?”

Now, peering out of the cave, I look out into the deepest blue I’ve ever seen, and the last thing I’m thinking about is ascending. One hundred feet ahead, visibility perfect, the trench drops off several thousand feet, down to 10,000 feet. A school of curious gray reef sharks poke snouts into the cave.

Out of the cave, adrift 40 meters below the surface, the ocean world moves past in a dizzying hurry. A finger hold here, another there, just enough to slow you down momentarily. Then you’re off, and fast, being sucked towards the lagoon by a racing current. The biggest danger is being caught inside a mascaret, a phenomenon produced when the swell or wind is traveling in the opposite direction as the current. The accompanying turbulence creates whirlpools and the sea fills with particulate, making it difficult to see, easy to get lost. Being thrown against sharp rock pinnacles jutting out from the valley side is another worry. But as Nanoa unfurls her orange float, signaling the Zodiac far above, we linger, grasping for one last finger, toe, knee, or elbow-hold, hallucinating on the rush of marine life skidding by like some kind of 12-lane traffic accident passing in slow motion.

COCONUTS

P

addling towards a seemingly vacant beach on Toau, a walnut-shaped atoll 100 miles south of Rangiroa, a voice shouts loudly out of the plantation palms. “Hello, My Friends!” Ugo??

No. It is Eliza, one of the island’s 10 inhabitants. She has lived here all her 50 years, in a two-room, plywood & tin-roofed shack along with her 62-year-old husband (Snow — “his relatives are royalty back in England, we think”) and one of her two grown sons, a 20-year-old called “100 Kilos.”

There are three ways to make a living in the Tuamotu’s. Fish. Copra. Black pearls. Eliza and her extended family – she’s related to everyone in a 100-mile radius – are into them all. Pens of big parrotfish sit off the nearest pass. Burlap sacks of dried copra – the white meat of coconuts, used to make coconut oil – stack up under a porch roof (the twice-a-month cargo boat that brings everything the islanders need will take them away). And in a hibiscus tree hang the black nets used to float pearl-bearing oysters 40-feet below the surface of the deep lagoon. This last economy, black pearls, is the lifeblood of the chain. An additional 10,000 people have come to the Tuamotu’s in the past decade (joining 15,000 already here) to participate in the boom. One result is that everyone now wants to have his/her own pearl farm, threatening the future market value of the shiny orbs which range in color from champagne to green, but rarely truly black.

Dressed in a blue swimsuit and gray shorts, sunglasses stuck into her thick black hair, Eliza has a wide, gap-toothed smile. Since she’s the first person we’ve seen since leaving Rangiroa she gets to hear the incredible story of how we somehow managed to leave behind all our freshwater. Five jerry cans filled to over brimming with 100 liters of the clear, fresh stuff. The only thing we truly need out here, the only irreplaceable necessity, and we left it sitting on a cement dock. She listens, nods her head, seems to understand our dilemma, but in seconds is waving good bye, howling to the dog she’s left behind to be our companion – Tyson – and zooming off into the sunset in her white-plywood speedboat . . .

. . . . only to return early the next morning, accompanied by “100 Kilos,” who hands a fat blue plastic jug of fresh water over the side of the boat as it skids to a stop in the sand. Eliza carries another gift – a coconut puller. As long as there are coconuts, you will always have water. But the freshest and wettest are the green ones high in the trees, which require a long pole with a metal hook to reach. Within minutes our self-sufficiency quotas have doubled. We can now fetch and open a coconut in 10 or 12 whacks, recognize fresh mangoes from 100 paces, open clams with nothing but a stiff knife. Only our spear fishing is lacking. Pedro has the only take so far, a fist-sized parrotfish that required more work to clean than it was worth.

Every day – and most noticeably, at night –we hear falling coconuts thudding to the ground with regularity. I ask Eliza how many times in her life she’s been hit by falling cocos. It seems like an inevitability, statistically-speaking. She looks at me as if I’m crazy.

“Never, of course!”

And why not?

“Because, silly, coconuts have eyes. Look at them! They can see if you’re underneath and, if you are a good person, they will not fall on you. I promise. In my family it has never happened!”

SUCKING CURRENTS & TIDES

T

he maaramu winds have arrived early this year, accompanied by rain and gray skies. Hunkered down on Toau under sodden tarps, paradise takes on a new glimmer.

But the kayaking doesn’t stop. We’d spotted a boat wreck on the ocean-side. Big, metal fishing boat split in two when it hit the reef. We could only guess at why: The engine quit and the boat was forced over the reef by strong winds? Night, and the captain never saw the reef coming? Hurricane?

To reach the wreck we must negotiate our way across the pair of fast-moving passes that connect the sea to Toau’s lagoon. Sails up, we move quickly from camp to the first pass. A strong wind at our backs, in the midst of the first, two-mile wide pass we find ourselves all-of-a-sudden being chased by eight-to-ten foot waves, which push the kayaks down one side and squirrel them up the next.

“My butt was definitely puckered through that,” shouts Pedro as we pull into calm waters on the slender motu that separates the passes. All five of us are now thinking about the return, paddling into those same seas, the constant risk being a flooding tide pushing us out of the pass and onto a wind-swept ocean.

The second pass is longer, calmer.

A half-mile walk through rising tidal pools and along a rocky beach leads to the wreck. Rusted and rotting, one half lying in the surf, the other 30-feet inland. Poking our heads into portholes and stomping, carefully, on flaking metal floorboards, the boat had long ago been stripped of electronics and valuables. We could only imagine the wild ride its crew had as it surfed heavily over the reef and ground to a halt, no doubt with pounding seas punishing it from behind.

When we return to our kayaks the tide has peaked, the middle of the pass a true mish-mash of competing currents, tides and winds. On the lagoon side, the current and tide are flooding fast towards the sea; mid-pass they are met by a mounting build-up of 10, 15, 20 foot crashing waves. Getting sucked into the middle of that would be ugly. The key to crossing safely is choosing a conservative line heading deeper into the lagoon than you might think necessary, in order to avoid being pushed into the midst of the now-raging pass.

Armstrong, a veteran whitewater kayaker but sea kayaking novice, goes first, carrying cameras. From where we watch on the near shore, it looks scary. Seemingly non-chalant he paddles just on the edge of the moving water. Then – as he nears the far shore – his paddle reps increase, making him look like a Roadrunner character, as he barely makes it to shore. His “scout” gave the other four of us impetus to increase the depth of our “V” when it comes our turn.

Successfully across the first pass, a worst-case scenario nearly spoils the day. On the verge of attempting to cross the second pass, the 8-10 foot swell now flowing out towards the sea, Armstrong flips and, with heavy camera gear weighting down his kayak, can’t right himself. And his PFD is strapped to the back of his boat. It is “worst case” because if others weren’t around to quickly help him stabilize his boat and get back inside, he’s afloat – without a boat – swimming through big waves, being pushed out into the ocean. Our only course of action would be to send young Nicks – the strongest paddler among us – in pursuit, in hopes he’d find him. Once rescued, most likely sans boat, the pair would have to sit outside the pass until the current swapped, which could be six hours, or two days.

“That was a wake-up call for me,” Armstrong said afterwards. “I’ve spent many hours in my river boat and never once worried about my ability to roll it back up. With these big boats I realize now that you have one chance to roll and that’s it. Otherwise the boat is filled with water and you’ve almost literally sunk.”

Everyone back in his boat and secured, the wind and rain pick up dramatically. Nicks eyes the pass coolly, as our most-veteran sea kayaker Willie judges it “dodgy.” Pedro and I are looking at the falling-down shack on the motu next to us, wondering if it might not make for a good camp. Choosing a marked angle out into the lagoon, straight into 20 mph winds, we set out. Though it’s only two-miles across, it takes 60 minutes of non-stop sprinting to get out of the headwind and cut towards shore. The highlight of the day is the glimmer of sun that breaks through as we paddle, followed by a double-rainbow stretching from sea-to-sea.

PEARL CITY

H

ow long can you hold your breath underwater? 30 seconds? One minute? Longer? Try it. Now.

Just off a mini-motu afloat in the sizable lagoon at Toau, in rough seas on a perfectly blue & sunny day, we’re testing our own lung capacity. Veldo, a 22-year-old black pearl farmer, is checking out his heavily laden panniers, each boasting a couple hundred oysters. They are strung along a thick, buoyed rope and he dives down, 20, 30, 40 feet, staying under for three, three-and-a-half, four minutes at a time. He’s checking to make sure the crates are secure, mostly against the oyster’s greatest predator – the turtle.

After a minute-and-a-half, our lungs are burning and we’re popping to the surface like corks out of champagne bottles. Veldo patiently waits down deep for our return. After a couple dozen dives we surface en masse and search the heaving surface of the sea for the bright yellow-and-orange plywood speedboat that we thought we’d tied to one of the buoys. Oh, there it is, floating away! A mad swim-sprint (by Veldo) catches the runaway craft and we’re off for the island.

Pamela is Veldo’s 22-year-old partner. It’s just the two of them, on this tiny spit of sand, nurturing several hundred thousand oysters. She is pretty and all business, loves Celine Dion, Shakira and Britney. “I hate Papeete, where I was born,” she says. “Too many people, too much noise, too much pollution.” She grew up on Takapoto and learned her craft on Apataki. Veldo is powerfully built (a burlap bag filled with sand hangs in his workroom, used as a punching bag), soft-spoken and prematurely graying.

Their connection to the world comes in two-parts: Satellite television, carrying 11 stations direct from France, and a powerful VHF radio that keeps them in contact with their eight neighbors spread over a 100-mile radius. They offer homegrown tomatoes and mint from their small garden; we trade Clif bars and Gatorade. It’s a fine little compound, three separate buildings powered by a gas generator and solar panels. On the beach, dug into the sand, is the propeller off the wreck we’d visited the day before. Turns out the captain fell asleep. The chatter on the VHF radio is non-stop today, focused on guessing at what time the Stella M — the twice-monthly cargo boat – will arrive. Veldo and Pamela are expecting a load of plywood to add to the exterior walls of their house.

For other supplies they occasionally make the 17-mile run across open ocean to Fakarava in their seemingly-flimsy 17-foot plywood boat. If the motor breaks down, or some other catastrophe stops them dead? “We put on our jackets, send up a flare, and turn on the VHF,” says Pamela. I can see them, standing side-by-side, he holding onto the wheel and the accelerator, she to the bow and to him, blasting through big waves, both hanging on for dear life as their fluorescent-colored boat rockets through the surf.

It’s a good little cottage industry they have. She grafts 400 oysters a day on a tightly followed schedule, between 7 & 11:30 and12:30 & 3. Three hundred of them will give pearls of some form, shape and color. She sells the pearls to occasional boats that find their way into the lagoon and to buyers from Tahiti and Australia. Twice a month they send a cooler of fish to his mother in Papeete; she fills it with fresh fruit and returns it on the next boat. Once a year they are visited by a French tax official, who looks at their books and assesses a tax.

She sees us back to our kayaks and in a phrase that carries a lot of weight coming from a local, refers to her little motu as “paradise.” It’s good to hear that not only palefaces regard this place in that light.

THE SEARCH GOES ON

J

ames Norman Hall co-authored a handful of books that introduced the notion of “South Pacific as Paradise” to millions. “Mutiny on the Bounty” is the best-known, as well as its siblings, “Men Against the Sea”, “Pitcairn’s Island,” “Hurricane” and more. A biography of the writer – and his writing partner Charles Nordhoff – is called simply “In Search of Paradise.”

“Grandfather came in February 1920 for the Atlantic Monthly,” Hall’s grandson Jamie says, looking from his house on a Tahitian hillside out over Bounty Bay. “His assignment was to write a tourist’s guide to the islands, for Americans. He, and Nordhoff, had been pilots during World War I and they were definitely in search of paradise. And they definitely found it. Of course they stayed …”

Jamie lives on family property and serves as curator of the James Norman Hall museum, an old family house just across from the beach from where Captain Bligh, Christian Fletcher and the rest of the Bounty’s crew first came ashore. Fifty-years-old and married to a Fijian, Jamie understands perfectly his grandfather’s role in “creating” a modern-day image of paradise. And the responsibility therein. He also has some insights into the historical characters the “Mutiny” books made infamous. (“It’s simple, really. They had made girlfriends here and most were pregnant when Bligh insisted they leave. The men wanted to stay, start families, not go back to England where it was cold and gray and they had not jobs. And where there were no vahinis. They wanted to stay in the islands. Who could blame them?”)

“When Grandfather and Nordhoff arrived here there was just a simple hotel in Papeete, with fantastic room service and fantastic food. The weather was perfect and they met a mélange of interesting people – British, French, German and Tahitians. No traffic. No television. No telephone. No radio. No noise. No pollution. It truly was . . . paradise.

“If they could see Tahiti today, they’d turn around and go straight back to heaven. They would not regard it as paradise any longer – too many people, too much noise, and too much pollution. Where might they go instead? To the outer islands, to where you’ve just been, to the Tuamotu’s. If there is a paradise today, that’s where you will find it. That’s where Grandfather would live today, I’m sure. Right smack in the middle of them!”

– EPILOGUE –

Our month-long paddle remains one of my favorite adventures, so much so that I’ve been back to Polynesia many times. But stay tuned! Our exploration of the Tuamotus was two-part. The initial two-hundred miles was explored by sea kayak, and we saw the rest of the thousand-mile chain by cargo boat delivering everything from cinder blocks and cd’s to frozen chicken and cigarettes to the remote atolls.

– CREDITS –

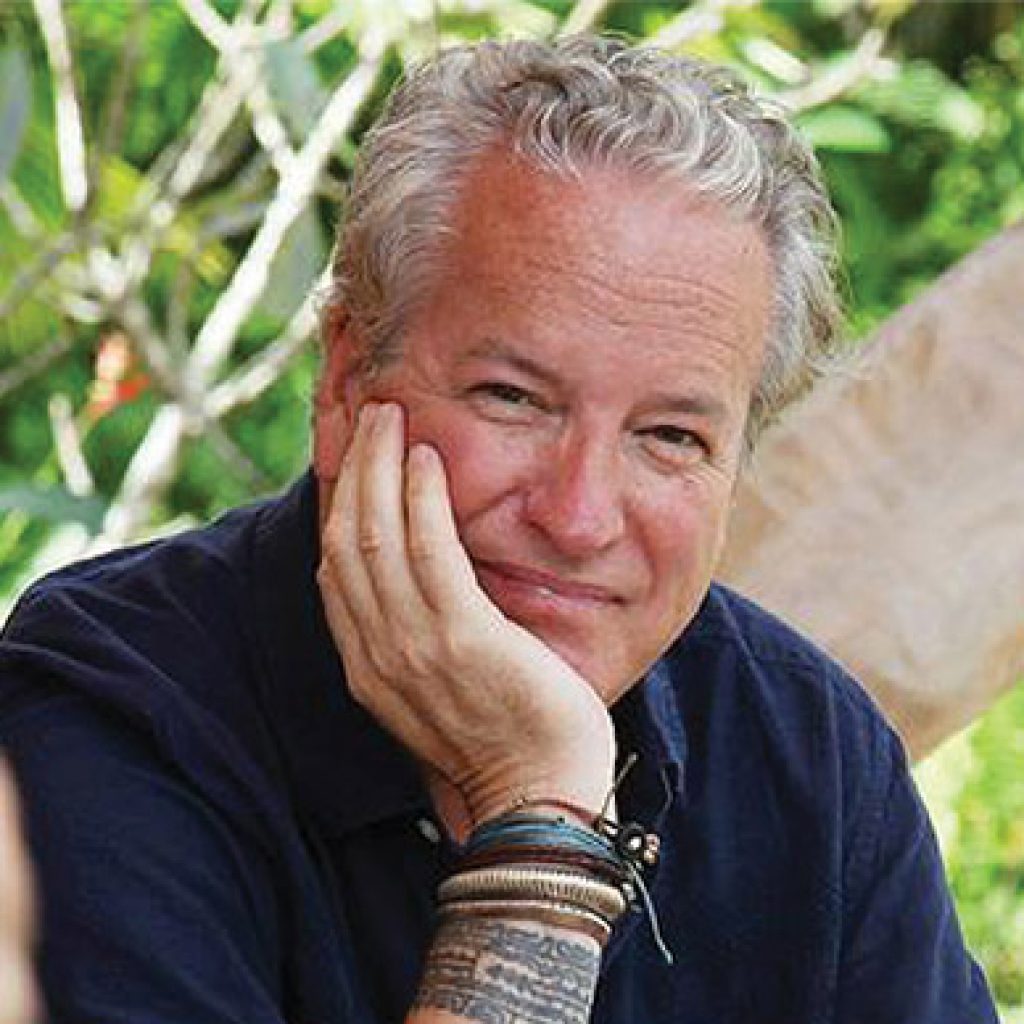

JON BOWERMASTER

Writer, filmmaker and adventurer, Jon is a six-time grantee of the National Geographic Expeditions Council. One of the Society’s ‘Ocean Heroes,’ his first assignment for National Geographic Magazine was documenting a 3,741 mile crossing of Antarctica by dogsled. Jon has written a dozen books and produced/directed more than fifteen documentary films.

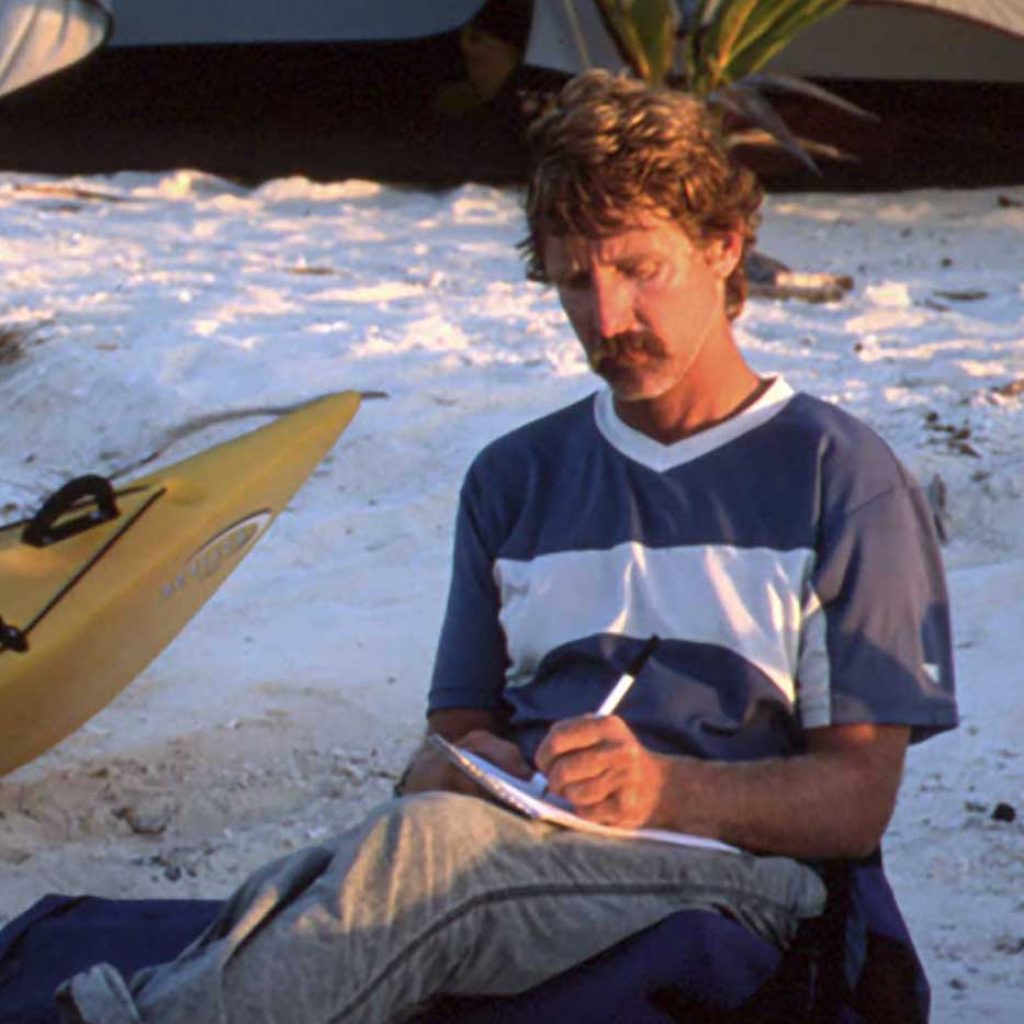

PETE MCBRIDE

Colorado-based PETE MCBRIDE accompanied me on five of the eight Oceans 8 Expeditions, though our first assignment together for National Geographic Traveler was set in Cuba. In recent years Pete has continued to photograph for National Geographic and many others and has become a true hero of the Grand Canyon, having rowed it and hiked it. Check out his films, stories and images at www.petemcbride.com

ALEX NICKS

UK-born videographer ALEX NICKS is one of the world’s great expeditionary whitewater kayakers, so getting him to travel with us in our, heavy, slow-moving sea kayaks took some convincing. He filmed four of our eight expeditions; check him out here, running the Zambezi: http://vimeo.com/47919375

WILLIE WILLIAMS

National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) instructor WILLIE WILLIAMS was an incredible addition to our team, taking responsibility for much of our daily logistics including food, cooking and always finding fresh water, a key resource in a place surrounded by the sea. Sadly, Willie passed away six years after our expedition, in 2008, from cancer.

JOHN ARMSTRONG

Camerman and filmmaker JOHN ARMSTRONG has filmed on all seven continents and here in the Tuamotus it often meant disassembling what in those days was a very large camera (a Betacam!) and storing it in various compartments in his 17-foot-kayak, all the while protecting it from salt and sand. Juan continues as a top Hollywood operator, based in Malibu, across the street from some of California’s best surfing.